![]() Guide: Thomas Cole’s “The Course of Empire”

Guide: Thomas Cole’s “The Course of Empire”

Linda S. Ferber, Vice President and Senior Art Historian at the New-York Historical Society, acts as a guide through Cole’s suite of five paintings in the videos below.

![]() Guide: Thomas Cole’s “The Course of Empire”

Guide: Thomas Cole’s “The Course of Empire”

Linda S. Ferber, Vice President and Senior Art Historian at the New-York Historical Society, acts as a guide through Cole’s suite of five paintings in the videos below.

![]() Guide: Modern Dance in America

Guide: Modern Dance in America

I had the pleasure of seeing Les Ballets de Monte-Carlo, the national ballet company of Monaco, perform a program of two long works, Altro Canto and Opus 40, at the Joyce Theater in New York City. Both works were created by the company’s director since the early 1990s, Jean-Christophe Maillot.

Maillot’s vocabulary is far from traditional ballet (although slippers and pointe shoes were worn by the dancers), and the dancers moved in ways that are highly unconventional: they dragged each other around the stage by the wrists, they stepped on each others backs, their limbs were sometimes extremely fluid or limp (creating an impression of passivity), and they often made extreme concave or convex shapes with their torsos (bringing to mind the contraction and release technique of Martha Graham). The movements were also often acrobatic in nature: in Altro Canto, the lead female dancer was off of the ground for several minutes, being lifted by and diving into groups forward and backward like a highly controlled crowd-surfer (one of my favorite sequences). All of this was pursued in a highly graceful manner, however, and was far from raw or violent (unlike the movement of choreographer Pina Bausch, whose work I watched just two days after this performance).

Les Ballets de Monte Carlo performing "Opus 40"

While I found this to be a compelling evening of dance that explored a range of movements and feelings in a way that felt original and sometimes unexpected, the pieces seemed to lack a cohesive structural flow. Strings of movements at times felt arbitrarily varied, and I found it difficult to detect a clear direction or an internal formal logic from moment-to-moment. At the end of a piece, I felt that I hadn’t been taken on a journey but rather spent time wandering between different facets of one place. There was a clear structural device in Opus 40: at the end of every music/dance segment, the dancers of the next segment—typically costumed in a different color scheme—would wander onto the stage, interrupting the ending of the current segment before the transition of focus occurred.

Altro Canto utilized a score of excerpted segments of Baroque music (recorded—no live music here), especially sacred music by Monteverdi, and sought to respond to the atmosphere of the music in a number of ways. Echoes often occur in the music—a solo violin line is repeated by an offstage violinist—and this was at times referred to onstage, with a duo of lead dancers downstage and and an echoing set of dancers upstage. Two singers would also sometimes be represented by two dancers, for example.

In "Altro Canto," the minimal golden lighting was intended to evoke candlelight (Maillot explained in the program that he associated candlelight with sacred music performed in cathedrals).

Generally, I felt that the dance was not always connected to or subordinated by the spirit of the music but it utilized the music when it pleased. The mood and vocabulary of the dancing did not change drastically in Opus 40, a selection of music by the avante-garde composer/vocalist Meredith Monk—stylistically extremely different from Baroque sacred music—so the dance’s connection to the music seemed to have more to do with pacing and phrasing than style.

The costuming played a large part on the visual impact of the pieces: in Altro Canto, half of both the men and women wore corsets and pants, and the other half wore tank tops and extremely poofy skirts—all gold-colored. The gender ambiguity of the costuming was intended to evoke the duality of masculine/feminine identity.

In Opus 40, the dancers were clothed in bright colors. Maillot’s program note refers to the piece as a return to childhood. While this aspect of the piece didn’t resonate with me, as the piece felt very adult and introspective, the color scheme was an effective allusion to playfulness and purity in simplicity.

![]() Guide: Modern Dance in America

Guide: Modern Dance in America

The period from about 1926-1942 is considered to be the golden era of dance in America. It was at this time the foundations of Modern dance were formulated and established and a vibrant canon of dance styles evolved.

Influenced by the new approaches to dance popularized by Denishawn, and ideas filtering in from the German Ausdruckstanz (“Expressionist dance”) movement, a few individuals—dancer/choreographers, as well as people who advocated and popularized their work—forged a repertory and methodology of dance that would be recognized as artistically legitimate by an enlightened public.

These “heroes” developed approaches to dance that would influence (and be reacted against by) the following generations to this day.

Helen Tamiris, trained in ballet, created dances that explored social issues and was among the first dancers to integrate influences from jazz and African-American culture, creating a suite of dances to Negro spirituals. She also choreographed for Broadway musical theatre. An energetic advocate of dance, founded the Dance Repertory Theatre and was key in establishing the Works Progress Administration’s Federal Dance Project, a government-funded effort to stimulate the creation of dance during the Great Depression. Tamiris believed in creating dance that would be relevant and politically motivating for the working class of America. [Watch a short clip of Tamiris dancing on DanceMedia.]

My main sources for this post are:

Mazo, Joseph H. Prime Movers: The Makers of Modern Dance in America. Princeton, 2000. pp. 13-34.

Reynolds, Nancy, and Malcolm McCormick. No Fixed Points: Dance in the Twentieth Century. Yale UP, 2003. pp. 1-10.

![]() Guide: Modern Dance in America

Guide: Modern Dance in America

Some characteristic works:

I consulted these sources in researching Humphrey’s work:

Mazo, Joseph H. Prime Movers: The Makers of Modern Dance in America. Princeton, 2000.

Reynolds, Nancy, and Malcolm McCormick. No Fixed Points: Dance in the Twentieth Century. Yale UP, 2003.

![]() Modern Dance in America is an evolving overview of some of the most important and influential choreographers/dancers, works, and movements in the history of Modern dance in America from the turn of the 20th century up to the present.

Modern Dance in America is an evolving overview of some of the most important and influential choreographers/dancers, works, and movements in the history of Modern dance in America from the turn of the 20th century up to the present.

![]() Guide: Music Inspired by Art

Guide: Music Inspired by Art

>Listen to the complete song cycle on this website

The poems were composed in strict meter and rhyme, and while some English translations recreate this (notably those by Sidney Alexander) I was attracted to the more prose-like translations of James M. Saslow based on their clarity of meaning and dramatic pacing. However, as I began work on the music, I found that Saslow’s word choice and syntax did not always work ideally with music—with the exception of the first selection in this cycle, which I found to fit perfectly and have used without alteration. For the other poems, I adapted the text into my own words, consulting Saslow and Alexander, and occasionally the original Italian (which I can’t read, but felt through with a dictionary and some guesswork!).

While I took a great deal of stylistic liberty with the language and poetic meter, I strove always to retain the essential meaning of the poems and to deliver Michelangelo’s metaphors intact. More often than not I have liberally truncated his complex, interweaving syntax into concise phrases that can be more easily understood in real-time performance. I hope that I have been able to adapt Michelangelo’s ideas into a form that might illuminate them in a new and meaningful way for the audience.

To give a sense of how similar (or dissimilar) the poems in this cycle are to the originals, here are excerpts from Michelangelo’s original Italian poems, English translations by a published scholar, and my own adaptations.

In this first excerpt, I makes the four lines of this stanza rhyme rhythmically (although the words do not), which allows for a “song-like” setting.

Michelangelo’s Original

Passo inanzi a me stesso

con alto e buon concetto,

e ‘l tempo gli prometto

c’aver non deggio.

Excerpt, poem 144 [Girardi numbering]

Translation by James M. Saslow

From The Poetry of Michelangelo, An Annotated Translation. Yale University Press, 1991.

I get ahead of myself

with a lofty and fine conception,

and promise it the time

that I’m not to have.

Nell Shaw Cohen’s adaptation (“The Years I Cannot Know“)

I plan for the time that I will not have

to realize a lofty goal.

I promise myself completion

in the years I cannot know.

In this next example, I took only the essential meaning behind the poem and dramatically altered the rhythm of the text in order to suit my purposes in setting the words to music.

Michelangelo’s Original

S’egli è che ‘n dura pietra alcun somigli

talor l’immagin d’ogni altri a se stesso,

squalido e smorto spresso,

il fo, com’ i’ son fattoda costei.

E par ch’esempro pigli

ognor da me, chi’ i’ penso di far lei.

Excerpt, poem 242 [Girardi numbering]

Translation by James M. Saslow

From The Poetry of Michelangelo, An Annotated Translation. Yale University Press, 1991.

Since it’s true that, in hard stone, one will at times

make the image of someone else look like himself,

I often make her dreary

and ashen, just as I’m made by this woman;

and I seem to keep taking myself

as a model, whenever I think of depicting her.

Nell Shaw Cohen’s adaptation (“I Become the Model“)

Sometimes one will make

the image of someone else

look like the image of himself.

So, I make her gloomy just as she makes me.

I become the model whenever I model her.

In the following example, I stayed much closer to Saslow’s language, choosing to collapse some of the poetic syntax into simpler phrases.

Michelangelo’s Original

sì che mill’ anni dopo la partita,

quante voi bella fusti e quant’ io lasso

si veggia, e com’ armarvi i’ non fu’ stolto.

Excerpt, poem 239 [Girardi numbering]

Translation by James M. Saslow

Excerpted from The Poetry of Michelangelo, An Annotated Translation. Yale University Press, 1991.

so that a thousand years after our departure

may be seen how lovely you were, and how wretched I,

and how, in loving you, I was no fool.

Nell Shaw Cohen’s adaptation (“A Thousand Years After We Are Gone”)

so that a thousand years after we are gone

all can see how lovely you were,

and how pathetic I was,

and that I was no fool in loving you.

>Listen to the complete song cycle on this website

Although Michelangelo’s poetry is not nearly as well known to the public as his sculpture, painting and architecture, it was an important facet of his creative life and appears to have been a passionate and somewhat private secondary form of expression for the artist (he was unpublished during his lifetime, and many of the poems were gifts to friends). Michelangelo worked in the tradition of Italian lyric poetry as defined by Petrarch and Dante. Echoing Petrarch’s Laura and Dante’s Beatrice, Michelangelo often addresses a woman–who may be imagined as the poetic representation of Vittoria Colonna, with whom he had an intense friendship (now considered by scholars not to have been truly romantic).

Michelangelo wrote over three hundred poems, many of which utilized imagery or metaphors from his primary medium of marble sculpture. Fragments of verse can be found in Michelangelo’s sketchbooks, scribbled on the same pages as studies for his masterpieces, showing that these two disparate art forms were complementary or intimately related in his mind.

The poems I selected for my musical interpretation of Michelangelo’s poetry and art, Revealed in Stone (2009) for tenor and piano, center around a few of the most prevalent and intriguing themes in Michelangelo’s repertoire: time, death, and the immortalizing power of art; the artist’s concetto (conception or idea) and the perfection of its realization; the reflection of the artist’s self in his creations; the tension between hiding and revealing, which relates to the subtractive process of marble sculpture; and a yearning for spiritual release, or elevation, from the human condition.

He alludes directly to this idea with a metaphor for sculpture as the earthly confinement of an enigmatic spirit (“I came down, against my will, from a great ravine / in the high mountains to this lower place, / to be revealed within this little stone.”).

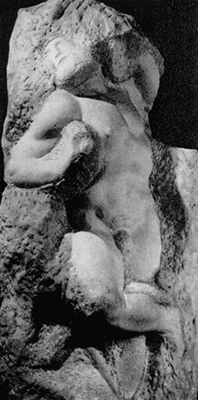

While Michelangelo is best known for masterpieces such as his David and Pieta, among the most compelling products of Michelangelo’s sculptural output, and those which most strongly symbolize the Neo-Platonic theme of the struggle to transcend physical form (alluded to in the poems), are the non-finito (unfinished) sculptures – particularly St. Matthew and the Slaves (works that were a major influence on Auguste Rodin).

These are vague, faceless figures that appear to be struggling to emerge from masses of marble. It is debated whether or not Michelangelo left them intentionally unfinished, but either way these are striking examples of the outstanding characteristics of Michelangelo’s art: dynamic, overwhelming strength veiled in melancholic beauty. This was the vision I had in mind as I searched for the mood and language of my music in Revealed in Stone.

Young Slave

Awakening Slave

St. Matthew

![]() Guide: Music Inspired by Art

Guide: Music Inspired by Art

Georgia O’Keeffe (1887-1986) is among the most noted American painters of the 20th century. She is well known for her abstracted images of flowers and her images of the New Mexico southwest scenery, which she loved and thrived in for the latter half of her life.

Georgia O’Keeffe (1887-1986) is among the most noted American painters of the 20th century. She is well known for her abstracted images of flowers and her images of the New Mexico southwest scenery, which she loved and thrived in for the latter half of her life.

Born in Sun Prairie, Wisconsin, O’Keeffe first found success in New York City with the support of photographer, gallery owner, pioneering advocate of Modernism, and future husband, Alfred Stieglitz (1864-1946). O’Keeffe discovered the beauty of the New Mexico landscape in 1929, and would splither time between the southwest and New York. After Stieglitz’s death, O’Keeffe moved full-time to her studio homes in Abiquiu and Ghost Ranch.

I’ve composed several works inspired by the life and art of Georgia O’Keeffe, including To Create One’s Own World (2009) for soprano, flute, bass clarinet, and marimba.

Listen to an excerpt from the song:

The text for this song combines a selection of short quotations from Georgia O’Keeffe’s writings, letters, and interviews, which I arranged. These excerpts are a brief but vivid articulation of O’Keeffe’s philosophy: a passionate commitment to self-expression, individualism, and creativity. In the song, the singer becomes O’Keeffe, and the mixed chamber trio of flute, bass clarinet, and marimba act as musical echoes and extensions of her sentiments.

To create one’s own world, in any of the arts, takes courage.

To create one’s own world, in any of the arts, takes courage.

Making your unknown known is the important thing.

I don’t see why we ever think of what others think of what we do — no matter who they are. Isn’t it enough just to express yourself?

I’ve been absolutely terrified every moment of my life — and I’ve never let it keep me from doing a single thing I wanted to do.

The days you work are the best days.

![]() Guide: Music Inspired by Art

Guide: Music Inspired by Art

I believe that painter Georgia O’Keeffe (1887-1986) achieved an important artistic ideal: to create new meanings, previously unrealized connections, and heightened ways of perceiving the world and filtering experience. I seek to do the same with my music video piece, The Faraway Nearby: to offer new insight and new ways of experiencing the paintings of Georgia O’Keeffe and her source material—to bring you into her world as I imagine it.

The Faraway Nearby is about seeing. When I look at O’Keeffe’s paintings of New Mexico, I am reminded of that remarkable landscape in a way that feels almost more immediate and more meaningful than the reality. I see the abstract shapes, colors, and compositional ideas that informed her interpretation of the visual world around her. I see the relationship to place that was immensely important to her, which she forged while hiking for endless hours through desert badlands. This piece is my attempt to create an immersive visual and musical experience that captures these qualities.

The video and music are closely coordinated in phrasing, development, and mood, and the structure of the music dictated my visual choices and pacing, both on a moment-to-moment basis and in larger formal concerns. Repetitions of the primary thematic section (heard at the beginning, middle and end of the piece) coincide with the image of Pedernal, “her mountain”. Pedernal is seemingly ever-present in the video, much as it looms on the horizon at Ghost Ranch. Here it represents O’Keeffe’s lasting presence, and her sense of spiritual ownership of the land. The musical atmosphere suggested to me by O’Keeffe’s visual world is a personal intuitive response which, I hope, speaks for itself.

The score to this multimedia video piece, inspired by the paintings of Georgia O’Keeffe, was composed prior to the conception of this video as part of a three-movement work for chamber quintet, Into nowhere (2010). I filmed on location in New Mexico in June 2010, and edited the video over the summer, adding animations and collaging visual elements evoking O’Keeffe’s aesthetic inspirations. The video received its premiere screening, with a live ensemble performing the music, in November 2010. Beyond the Notes: Music Inspired by Art will be the second time the piece has been screened in public, and I am seeking additional screenings (with live performances or pre-recorded score) and gallery installations for this piece.

Production of The Faraway Nearby was funded in part by an Entrepreneurial Grant from New England Conservatory’s Entrepreneurial Musicianship Department.