![]() Guide: Modern Dance in America

Guide: Modern Dance in America

While many dancer-choreographers of the second generation (such as Jose Limón) continued to develop the traditions and techniques pioneered by the “Big Four” (Martha Graham, Doris Humphrey, Charles Weidman, and Hanya Holm), there were some who chose to break away from these ideals and establish new and unorthodox approaches to dance. Several of these young avante-garde choreographers—including Merce Cunningham, Paul Taylor, and Alwin Nikolais—apprenticed and established their careers in the pioneering dance companies, but eventually struck out on their own to create works that challenged the audience’s expectations and asked the question: “What is art?”

Among the most influential of these radical second generation choreographers was Merce Cunningham. He is said to have single-handedly invented aesthetics and philosophies that set the scene for the postmodern choreographers who would follow him (especially the Judson Church group), as well as new forms of performance art and avante-garde art.

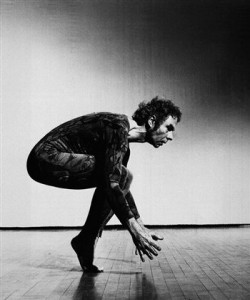

Merce Cunningham (1919-2009)

- Renowned as one of the greatest and most influential choreographers of the 20th century, Cunningham was also an accomplished dancer. He appeared onstage into his 60s.

- He choreographed a total of over 150 dances and 800 “Events”—performances well suited to unconventional spaces (gyms, armories, etc), which combined elements of dance, scenery, and lighting in unpredictable ways.

- Cunningham is notable for having impacted artists outside of dance with his progressive approach and through his extensive interdisciplinary collaborations with visual artists (including Robert Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns) and musicians (including John Cage, Christian Wolff, and Morton Feldman). His collaborations produced an influential body of work in music and visual art as well as dance.

- Cunningham was forward-thinking. Late in his career, he experimented with using a computer programs and motion-capture technology to create elements of his dances. Before he died in 2006 he created a “Legacy Plan” outlining how he would like his company to be run and left a thorough archive of digitized information, plans, and films preserving his work.

- Born in Centralia, Washington in 1919, Cunningham began dancing professionally at 20 years old with the Martha Graham Dance Company after having studied with her at Mills College. He admired and learned from Graham, but wasn’t convinced by certain aspects of her work—particularly the idea that every movement in a dance had to have a “meaning.” He was interested in exploring the mechanics of movement and the possibilities of the art form detached from specific emotional and psychological connotations.

- His first solo show came in 1944, and he formed the Merce Cunningham Company in 1953. He left the Martha Graham Dance Company in 1945 after having originated several important solo roles with her company (including the preacher in Appalachian Spring).

- Cunningham based himself in New York amidst a hotbed of avante-garde art and thought, and made a living by performing solo dances and music with his partner composer John Cage around the country. At first, his work was not readily recognized by audiences and critics. From the late ‘50s, some of his works began to picked up by noted companies, including the New York City Ballet, and his company appeared in international venues.

- By the late ‘60s, his work was no longer considered the cutting edge: the Judson Church group had begun pushing radical experimentation and the question of “what is art?” even further.

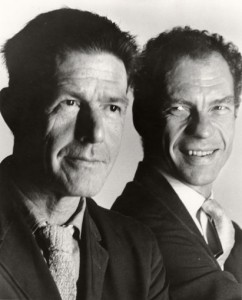

Cage and Cunningham

- Cunningham’s most important ongoing collaboration was with his life partner, John Cage (whom he first met in his late teens, when Cage was playing accompaniment for dance classes in Seattle.) They began working together in 1942.

- Together, Cage and Cunningham explored a radical new approach to the relationship between dance and music: dance and music co-existed within their pieces, but were not directly coordinated or matched in time and were created independently of each other. (In this interview with Cunningham and Cage from 1981, the two discuss their collaborative methods.)

- They both used chance procedures in constructing their works—that is, they used unpredictable factors (rolling a dice, tossing coins, etc) to make decisions about certain events within a piece (e.g. sequences of movements).

- Cunningham’s dances abandoned conventional elements of dance such as narrative, climax, or associations with things other than the movement itself. Similarly, Cage broadened the conception of music to include a wide range of non-instrumental sounds (and even silence itself) and did away with traditional concepts of harmony, melody, form, and instrumentation.

- Zen Buddhism was one of Cage and Cunningham’s major influences (before there was popular interest in Zen amongst young people in America). They admired Zen’s discipline, ideas about silence and void, and escape from patterns of thought.

- Their philosophy and approach to the creative process were also influenced by the I Ching, an ancient Chinese text, and the German philosopher Nietzsche.

- Both Cage and Cunningham wanted to create works in with the audience could become a part of experience—to leave elements of the dance or music open to the personal interpretation of the listener-viewer. Any number of different reactions to his dance were valid, as far as Cunningham was concerned.

Much of the above information is drawn from:

- Reynolds, Nancy, and Malcolm McCormick. No Fixed Points: Dance in the Twentieth Century. Yale UP, 2003: pp. 354-370. Print.

- The official Merce Cunningham Dance Company website.

Recommended Viewing

- Excerpted performances by the Merce Cunningham Dance Company from the 2011 Legacy Tour on YouTube: Second Hand (197o) with music by John Cage and costumes by Jasper Johns. Roaratorio (1983) with music by Cage and decor by Mark Lancaster.

- Changing Steps (1975) video version directed by Cunningham and Elliot Caplan: part 1 – part 2

- Mondays with Merce – a documentary TV show exploring Merce Cunningham’s work and guest choreographers.